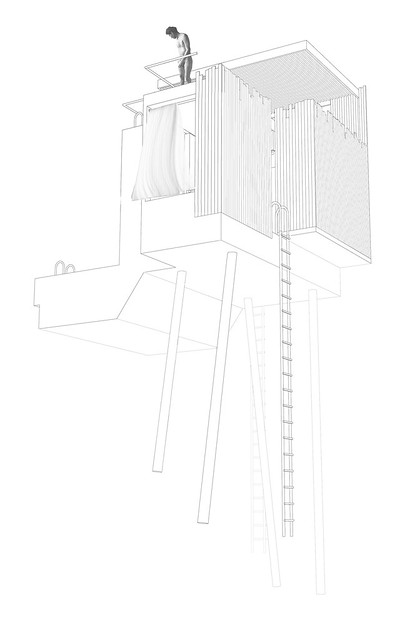

The house for doing nothing

The Žižek residence is proposed more as a call for discussion about architecture and politics today than as a specific design concerning a small house or a complex of houses in an isolated Greek island. The house answers one of Žižek's quest for withdrawal but in the same time it seeks a way to reenter a political discourse. A possible Greek architectonic example is elaborated today within Greece's controlled bankruptcy, following the Slovenian theorist's consultation. Žižek writes in his Violence book (Picador, 2008):

“A critical analysis of the present global constellation- one which offers no clear solution, no "practical" advice on what to do, and provides no light at the end of the tunnel, since one is well aware that this light might belong to a train crashing towards us-usually meets with reproach: "Do you mean we should do nothing? Just sit and wait?" One should gather the courage to answer: "YES, precisely that!" There are situations when the only truly "practical" thing to do is to resist the temptation to engage immediately and to "wait and see" by means of a patient, critical analysis. Engagement seems to exert its pressure on us from all directions. In a well-known passage from his Existentialism and Humanism, Sartre deployed the dilemma of a young man in France in 1942, torn between the duty to help his lone, ill mother and the duty to enter the Resistance and fight the Germans; Sartre's point is, of course, that there is no a priori answer to this dilemma. The young man needs to make a decision grounded only in his own abyssal freedom and assume full responsibility for it.

An obscene third way out of the dilemma would have been to advise the young man to tell his mother that he will join the Resistance, and to tell his Resistance friends that he will take care of his mother, while, in reality, withdrawing to a secluded place and studying...”

Nevertheless the character of the Žižek residence even if it is proposed as a place for withdrawal may finally refer to a permanent, voluntary isolation. The Slovenian thinker proposes some distance from the world (a strategy that would "resist the temptation to engage immediately", a proposal to “wait and see” and have the opportunity for "a patient, critical analysis" after the voluntary withdrawal); nevertheless the house shows that, in some cases, the option of stepping back in order to have a distance from society is already problematic from its nowadays setting. The house is of course proposed as a place of literal withdrawal: in the same time, (and I am formulating here already my answer to Léopold Lambert) nothing seems to promise that there is a possible return to the condition that the house declines. The negation of society that the house proposes is in the same time constructing a new community order. The condition of the Žižek's house creates, while it is introduced as a process of withdrawal, different layers of impossibilities to escape the new social platforms that have already moved into the house, (not only in this exotic residence but in many houses) some years ago. The particular manner of withdrawing the house proposes already organizes an intermediate state, structured in between the absolute private sphere and the public function that melt in the inhabitation of the Internet. If we understand seclusion as a step back to the private, then we may agree that what was normally understood as a step back strategy yesterday does not apply today: no way out of this area seems possible. The house is designed as a confinement place, chosen deliberately. Žižek supposes that a "wait and see" strategy may promise anew a political future. But does his opinion present a possible way to invest upon the role of thinking today? Can we save the process of thinking by investing again in the same concept that made it valuable in the western past? The world theory (θεωρία) in ancient Greek describes a way to understand reality from a distance, the way to contemplate things from while we are distant to them in a way that we cannot touch them. The theoretical aspect of reality is related to the possibility of viewing from a distance. This distance that is necessary for a theoretical thought seems difficult for the nowadays Žižek's "withdrawal hero". The way the humankind (in its global north version) relates to its present through the inhabitation of the "Internet living archive" needs an analysis that would invest to the affirmation of the impossibility of distance. It seems that what Žižek presents as the precondition for any serious political position describes also a structural impossibility for the place of withdrawal today to create a distant look. We request a distance from things, we schedule a house in order to obtain this result but this house only shows the impossibility of the scheduled distance. The meaning of "wait and see" strategies is -in this background- ambiguous. The cancelation comes together with the project. Does Žižek mean that after some "images of a changing world" are formed and after some "political thinking" is performed, we could be able to return to the world or at least judge about its problems, propose possible ways to treat the problems in a pensive way? Or does he suggest that this distance is a prerequisite for any intellectual operation? In both cases this house organizes the distance from things as an impossible construction, in many senses: its interior space is produced as an idiosyncratic impossibility of distance that rules any political question concerning the global north. The Žižek's house is a counter project in its "first" reading: it proposes the negation of Žižek's idea; the glorification of withdrawal in the post network society of the global north may propose a problematic task, not because such a strategy is necessarily wrong but because the possibility of creating a condition of withdrawal seems complex today.

The attitude described by Žižek is not determined uniquely by the refusal of commitment to the community: there are many ways for doing nothing. We can retire to refuges in different ways. The withdrawal should not be seen as a political attitude per se but already in its political context. We recall three literary heroes of withdrawal. The first shows a different way to conceive “doing nothing”, in antithesis with the hero of Žižek. Jean Jacques Rousseau describes himself in his Rêveries du promeneur solitaire in a happy condition of isolation, in the almost deserted island of Saint Pierre that some call "l’île de la Motte". Rousseau locates a kind of happiness on his isolation days on the island. “Far niente”, the inactivity of this period is the biggest pleasure he experienced, present in all its sweetness. Devoted to inaction, he could not hold any communication or correspondence, and yet this period is described by Rousseau with great nostalgia. The inertia of his voluntary exile to a place where the author is hiding safely offer delight and a distance from community matters. While the withdrawal is described as enjoyable, it cannot be associated with any technique of responsibility of a political philosopher. Rousseau does not expect the distance to help him recognize new common problems or investigate anew about politics. He lives on the island in order to avoid the community which is presented as a menace and he enjoys this pause of the community life as a happy, early death that makes the hero’s problems disappear. Žižek's hero is not a hero of the “far niente” neither is he negating the community.

The second "withdrawal hero" would be Ivan Gkontsarov’s Oblomov, described in the novel that bears the hero’s name, published in 1850. Within the narrative we meet Ilia Illich Oblomov, a young nobleman, unable to take important decisions or undertake any significant actions. In the evolution of the novel he rarely leaves his room or bed: he stays in bed for the first hundred pages of the text. The book was considered as satirizing the noble class whose social and economic situation seemed problematic in the mid 19th century in Russia. Some laziness or inactivity, a reference to laziness was an important feature of the Oblomof’s withdrawal. And yet no laziness would characterize the Žižek’s "withdrawal hero" within the “living archive of the Internet”. The "pause for reflection" that forms Žižek’s hero has nothing to do neither with a hero of laziness nor with an emplematized hero who consciously refuses of work, as proposed, for example, by Paul Lafargues in his Right to Be Lazy. Labor today is structured differently than in the past. Labor through the Internet often diminishes the importance of spatial factors, it disturbs the oposition between working space and residence. As noted by Negri, labor tends to be determined by an immaterial condition. Franco Berardi also notes that labor is increasingly depending on cognitive functions. The immaterial labor of cognitive functions detaches the working man from the workplace. The work may occur indoors, within the space of withdrawal. The Žižek’s "withdrawal hero" in the present condition may be a normal working human.

The third "withdrawal hero" is the Des Esseintes coming out of the novel À rebours (Against the Grain or Against Nature) of Joris-Karl Huysmans. Des Esseintes decides to retire and devote his life in rest and in intellectual and aesthetic pursuits. Des Esseintes is presented as an eccentric, reclusive aesthete and Antihero: he dislikes the bourgeois society of the 19th century and attempts to withdraw into the world of art and the work of his own creations. In the last lines of the novel Huysmans compare the hero's "return to human society to that of a nonbeliever trying to emrace religion". The community appears impossible after the withdrawal. The hero of the house for doing nothing meets necessarily with the community since his withdrawal is radically transformed from the setting of its rules.

The hermit condition in the case of intellectuals to whom we turn our attention today is described through an impossible destination. Firstly, the Žižek’s hero cannot find a “correct” place "outside the community." We do not control even the meanings of such a concept today. Secondly the Ziek’s "withdrawal hero" cannot form the "external perception" as is required by hypothesis : he is defined by a lack of exteriority. Žižek's hero is the hero of impossible withdrawal because he lives in the area where the private became blurred with the public.

Withdrawal is either an impossible task or a necessary condition for the creation of the nowadays community. Léopold asks about the ephemeral character of Žižek's house as a seclusive place: a possible return "back there" may be very impressive. Nevertheless I am very skeptical about the character of this glorious return. The most important factor, in the design of this house would be that (from a particular point of view) it shows a voluntary confinement place. Nothing seems wrong in the withdrawal it organizes since it is performed as a voluntary entrance into an invisible community. Between a person and the community there is no clear limit, if we consider a person as a user of platforms and the community as a function of answering to given protocols or rearranging archive entries. From this point of view a political thinking would have to consider a future of politics in the archive.

The tower of Babel and the open dispersed agora / The system of interpreting a text today may take under consideration the conditions in which any interpretation is performed. We are used to meet people through texts, through tags, through invisible communities and we are also used to see people gathered around images. Discussion in this condition (as a possibility of any transaction between personal computers) forms an always open space; nevertheless, a discussion paradise of an open dispersed agora (that Ethel Baraona Pohl mentions in her post about the Žižek’s house) can also be described as a Babel tower of the common. None of those two different interpretations of the Žižek’s house architecture is privileged. We cannot argue that the Internet proposes a dispersed agora without adding that this agora is not exactly formed as a system of discussion but as a system that always already archives the discussion it generates, proposes its results as partial views, stores them over other similar, and finally makes them difficult to confront. Political decisions in this background can mainly be engagement strategies similar to the ones Žižek refuses in order to withdraw. The Internet discussions are by definition flexible left-overs like the one we are producing now together with Ethel and Leopold, using a foreign language that we all three cannot handle without difficulties. We cannot say neither that the Internet is a contemporary Babel, we cannot demonize it without adding that there are those characteristics of the Internet that can fix open platforms where everything can be posted, rarely in the form of discussion (as it happens now after we settled a chosen scenography). This negation to conclude about Internet, (to refuse to judge if it is a terrible thing and neither consider it represents the heaven of an open agora) is a prerequisite acceptance for reading the Žižek’s house project. Architecture in the condition of the Internet is not simply the creator of a "physical", "empirically experienced" environment; we would reduce the power of architecture if we only conceive it as a function of a "stable, existing" environment. Architecture today is a word to describe the complex systems that form backgrounds for human actions. Architecture would have then to be shaped as a coordination of both sides of the living areas: from one side the "empirical living of the real space" and from the other side, a living that investigates and perform in another interior space where we undertake actions through the web; specifically by answering to the web's different platforms. Does this design of Žižek’s house handle the totality of the matters, posed through such a wide investigation? It cannot. The design can only give form to a wide cockpit. It proposes the inhabitation of a cockpit with a particular relation to the materiality of a culture that understands the human body as a remain of a visual civilization. The uneasiness of such a relationship of space to the human body is also to be treated by the design of the house. Can we think about a cockpit as a place that has a reason "per se" to exist, without taking account of the destinations where it leads us? A cockpit is always a place that has prepared the conditions of a flight; what if this flight becomes the norm of the user? The cockpit becomes then a necessary condition of an unavoidable body, a space that treats the body functions as the excrement of the network activities. We only see in the house the remains of an intellectual life that is rendered invisible through a constant presence in the web. The Žižek’s house undertakes the role of interpreting a provocative fragment of an essay. It does so by unifying the two pieces of the user's experience, the life in the web and the life out of it. The house was always a space of a pause, installing a rupture in the time of the community. It represented an exit from the community. The Žižek’s house is no longer conceived as a space of a pause. The pause is not to be inhabited any more. The pause may be now an exit of the house, an exit of the net. The pause may be a necessary return to the old concept of the world. This would be the new exotic of tomorrow. Inhabiting the house is here identified to an idiosyncratic seclusion in the invisible communal space in which infrastructure, labor, entertainment, community networks and intellectual contemplations are melted in a unified sphere. The house is conceived as the mere ground of this sphere. It may sound normal that if we follow Žižek’s exhortation for "doing nothing" we may return home. Nevertheless today's homes for the humans living in the global north are not such places. If the "withdrawal hero" does not accept this kind of place as a secluded place for studying, what other possibilities could he have? If the Žižek’s house is replaced from a primitive cave or a unconnected spot, its resident will not be able to contemplate an important part of the society; in the same time the Žižek’s hero will be unable to judge about a changing society or perform any political investigation concerning it.

Stepping back is not exactly the condition that negates the networks. It is the function that the network needs in order to be created. While the limit between the network and its outer space is problematic, the question of political intellectual awareness seems also changed. The system of interpreting today's "home culture" could include discussions founded on net communities, performed through particular platforms that in the same time take advantage of the role of images. (I read here critically Richard Sennett: I do not think that the new home culture is necessarily linked to a decline of the political. A new political may be born from the conditions of the Internet) The question would be if it would be productive for future discussions to propose built environments as this "house for doing nothing", entering with rush into fields that show quick realizations of hidden intentions. The Žižek's text can be elaborated in order to conclude into an architecture. This architecture is, from one point of view, evident, through the plans and the images that describe it, and from another point of view the same architecture cannot be anything without an internet discussion concerning it. Three users write each other about their everyday experiences while they look in this idealized seclusion place. What is exotic in this easy communication? From a certain point of view the present discussion shows that the citizens of the global north are always already in Žižek's house condition: they are defined by similar settings.

Inaction/ This project undertakes to extend an investigation on inaction; the "raison d'etre" of Žižek's apartment is due to some nowadays modes of inaction. A cynical description of the city after the substitution of many of its functions through the Internet is a prerequisite for this investigation. The notion of political responsibility cannot be the same as before; a gap may interrupt its history. The changes in the concept of identity and its new definitions through the idea of "presence in the web" will determine this new phase of responsibility. If we understand the new possible cities as populations of secluded refuges that may look like congregations of well equipped, networked computer spots, we may need new descriptions of citizenship and of the communities that could replace the urban conditions of the past. The theoretical tradition of responsibility (as epitomized for instance in Levinas' or in late Derrida's works) gives an account of the preconceptions of philosophical thinking needed for the formalization of a political attitude within a community: an interesting part of this philosophical bibliography concerning "responsibility" was projected towards political theory. This theoretical past would need re-elaborations; remodeling the concept of responsibility and rejecting part of its tradition are related to the condition that the Žižek's house. The "house for doing nothing", also proposed as "the responsible house", is published in order to formulate a complex question concerning an attitude that does concern mainly a response to "not real things", a particular engagement to "entries that describe absent things" without needing the reference to any "prototypes". How can we think about responsibility with a new broken concept of identity that does not correspond to the civic identity, with no signature charged for the responsibility of the evolution of things, with a poor world populated by things and a rich world determined by an accumulation of conscious representations.

Difficulty to be patient and theorize / It is structurally difficult to ask for a "patient, critical analysis" of the situation we live in nowadays for three reasons at least. From a first point of view: the wind of global social changes poses practical problems regarding this need of deceleration; in a battlefield, in an open procedure of undetermined fights there is usually no time to install thoughtful distances from facts, especially in the case that rapid changes occur; we do not have the luxury for the necessary step back that could permit any intellectual preparation of thoughtful actions. This first argument is of course similar to the banal proposition that Žižek tries to avoid. Nevertheless let's consider that this position has a right to exist today: it is difficult to avoid the urgency of the evolving situations by a mere negation of them; we have a good example here in Greece. From a second point of view the imposed distance is formed through an idiosyncratic image of the exterior space that tends to be identified to an interior: a series of platforms can represent the exterior space, before it is posed as a problem of representation. The exterior space was conceived as a problem of representation. Today, exteriority is formed as a series of different representations. The networked civilization forms individuals who cannot really get out there, they are not supposed to question unformed fields; in this sense the users of the Žižek's house cannot reach any possible exteriority. They experience a phenomenon similar to the Plato's Cave of his Republic but seen now as an inversion: the cave has no exterior space. The most radical exteriority today is produced as a construction of the "unseen": some archived schemata, some digital landscapes soon visitable through the Internet form its matter. The distance from reality seems to produce the conscious, common and permanent core of the experience of reality "per se". Reality in this condition seems to be an always consciously distant, already represented world.

From a third point of view a "patient, critical analysis" of the situation we live in nowadays conditions would also be difficult because we would need a concrete place with the characteristics that Žižek needs in order to construct the political attitude of a thinker. The neutrality of a house of yesterday is not possible in our residences today. Maybe space lose its privilege of hosting political action within this condition; political actions may not happen any more in the world we traditionally form as architects. But where would then be this political observation place? Where would be this society we cannot configure? If a political attitude has to be formed through the elaboration of a distant view, the lack of distinction between distance and proximity could pose structural problems to its performance. At least this would mean that when we design the house for the "withdrawal hero", we do not consider his political action performed in the correct place; such a place does not exist; we will not expect to see his action deployed there nor in any other "pragmatic environment"; it may be performed elsewhere; we can neither configure the observation point from which the task of observing may be practiced; we neither see the exact target of such an observation. If thinking can still address political matters, it is at least rendered problematic in the condition of withdrawal: it cannot happen if the structure of it includes the confusion between figure and background, between the user and the community; or it may happen in a different format taking account of this other type of inhabitation of "the common" we experience. Thinking cannot be performed in a field of predetermined schemata. Thinking is read for Žižek as an abstention from the "real society" even if "the society itself" lost its meaning in various ways through the last decades. A consciousness concerning the loss of "society structures" is the most intimate core for the fabric of the Internet society "itself". A barbarism may prevail in the first possible future of a multiple, thoughtless "platform making". "Exteriority" is its first important loss. "Exteriority" in this background can only be proposed through the image of a battle field or in terms of a video game. Thinking loses its meaning whilst there is no image or visible narrative proved valuable as a representation for it in this new condition. Thinking as a nowadays human act has no convincing imagery, no slogan, its future depends to inventive graphic strategies. The civilization of writing in the form that we know it may be in "another last phase". What this loss of meaning for thinking would inaugurate? Why do we miss already the rational elaboration of western sociality so quickly and anew, after some centuries that a society of organized rationality was a western civilization target? We may propose answers to this difficult question before we undertake judgments concerning theory and action. What would be the meaning of theory today? What would be a theory without truth? If the concept of "inhabited platform" may be the analog of a city apartment, and if a congregation of platforms may already form invisible cities where every one is already leaving, who is really the actor of these new environment? Who is the actor of this house for doing nothing? The hero of the Žižek's house would be a time function, inhabiting different platforms. The actor is not a simple user but a serial, multiple "person" constructed out of an accumulation of participations in different Internet platforms.

Heterotopia / Ethel proposed the concept of hetero-topia to regulate an investigation about the house for doing nothing and the inhabitant. It is true that in the Foucault's text and in the bibliography that is linked to it, many thematic areas linked to the Žižek's house are present. Ethel insists on Foucault's “fifth principle”, where "he describes heterotopias as a system of opening and closing that both isolates ... and makes ... penetrable" the spaces that constitute them; it is true that such a description seems to be very suitable for Žižek's house. In the same time we have to do another structural remark of some importance, concerning the social field and the place of heterotopia inside it. We may put it this way, by a necessary simplification: Foucault's description of some heterotopic places is interesting because he compares some privileged or sacred places to some dreadful institutions of western modern societies. "Privileged or sacred or forbidden places, reserved for individuals who are, in relation to society and to the human environment in which they live, in a state of crisis" are compared with some "heterotopias of deviation" : the spaces for adolescents, menstruating women, pregnant women, the elderly" are compared with "rest homes and psychiatric hospitals, and of course prisons, and ... retirement homes" inscribed in a field of the heterotopic side of modern life. A crucial characteristic of heterotopias is linked to a rupture that distinguishes them as isolated places, cut from the everyday life. They do not perform within the everyday flow of time that any society tries to prove as the core of its normality; they occur within the excluded heterochrony of exception. We may quote Foucault:

"Heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time - which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies. The heterotopia begins to function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time. This situation shows us that the cemetery is indeed a highly heterotopic place since, for the individual, the cemetery begins with this strange heterochrony, the loss of life, and with this quasi-eternity in which her permanent lot is dissolution and disappearance".

Heterotopia cannot be defined as a simple banality of the everyday. It marks a cut to the everyday, we need a time gap to enter its world. And this is the problem that is presented through the Žižek's house. It proposes a negation of the everyday but it fails to constitute it. The negation of the everyday itself forms the everyday. The house intends to mark a difference from the everyday, to form an exterior world, but no, it cannot: it brings its inhabitant again in a banal world where the setting it proposes is known; everything is included in an interior; the exterior of the house is an interior homely function. In this place we have nothing to escape from. In the world the house proposes we are already used into escaping in "its own" manner. We may confess that some of us already live in the condition of escape as if there was a homely character in "escape itself". We inhabit escape. This house that is proposed as an exotic seclusion place is very common. The community of today is structured as an accumulation of such seclusions in the culture of the global North. The exotic land of elsewhere is identified with the most intimate center of the house. The Žižek's house, in this perspective, cannot be a heterotopia; maybe this is the most important problem it shows. It is formed as is a tauto-topia, a permanent symptom for any locus in the global north; a symptom that identifies the social with a number of secluded inhabitations. The social here is symptomatic, it is ruled by the withdrawal that Žižek poses as a precondition for a personal critical return to a social thinking. The house forms a heterotopic field but it is not proposed as such. What is important in this house is that a particular heterochrony is now installed in the core of the constitution of everyday life. We read again Foucault when he insists on this heterotopic character of the garden: "The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world". Couldn't this be proposed for Žižek's house? The house gathers some major heterotopic charasteristics. Yes, but in the same time the house claims that the nowadays global north society is constituted by an internal distance to itself. An uncanny generalization concerns this idealized exodus place: the house creates a simple image for the permanent condition that rules the everyday character of life; it proposes (while it is presented as an example of exception) a total narration for the everyday. Žižek's house is not as exotic as it should be; driving oneself out of the society is not a heroic operation; the seclusion that follows the negation of the community seems to be now the fundamental cell of the common; the house fails to provide the step back to the "withdrawal hero", because it represents in the same time the move toward seclusion and the openness to the community. In the same time its inhabitant would never be secluded, could never withdraw from the social even if this was the reason why the "withdrawal hero"'s refuge would be built. The inhabtant of this house is always already in the condition of community, experiencing nevertheless, in the same time, a permanent withdrawal. Considering the civilization of the global north, Žižek's "withdrawal hero" could be the most common person of the everyday life: withdrawal is the cell whose multiplication creates nowadays communities. If this is the presupposition of a political thinking (a distance from the social) and if today's sociality is defined by this distance then we will miss the opportunity to think because of a architectonic problem. This condition that is constructed as a house of thought, is structurally an observatory that cannot observe the field it is supposed to contemplate from a distance. The inhabitation of the distance is Žižek's house most critical characteristic. If we inhabit the distance from the social, if this inhabitation characterizes today's online sociality, we would be trapped in an interior with no limits. An interior with no limits has obviously no way out, no exit. Sociality in this case may be a big ensemble with single rooms of secluded people. If the seclusion place coincides to the idea of a permanent exoticism we may miss an observation point, necessary for any exterior contemplation of things and we may miss theory.

This house would have to be proposed as an exit room. It could be a heterotopia if it was a real place of escape as Žižek wanted it to be. But it is designed to form a question. Is it so? It engenders escape, keeps escape as its permanent program. But in the same time this escape would have to be permanent and therefore it may structurally be identified to its opposite, the enclosure in a place where it is impossible to escape from an "escape program". The world "escape" has a global north nowadays meaning. Escape can propose no exotic options any more. Seclusion, in this case, proposes neither a solitary attitude. The isolated house is not excepted from the community. Nevertheless, a city apartment was normally conceived as a part of a whole; the city was a system of congregated, categorized apartments: the apartment was the particular part that corresponded and represented the individual's position in the city and a sharing strategy of a finite land. Geometry is crucial for a city because it is introduced in order to count the surface of the land and calculate the different systems of sharing that give birth to different city planning strategies. The city was composed as an analogy to an archive, concerning this exact reference to a finite landscape: the city inhabitant's role was related to this particular belonging that was related to the apartment's status.

The responsible house seems to be formed by a negation to this "city sharing" condition. Its prototype is not produced out of sharing an existing finite land but out of an image of a house in an "exotic" infinite landscape similar to the video game interfaces we encounter in the Internet. There is no finite surface to share determining this project: the land it is proposed for could be any land. In an Internet city the sharing options for the space seem based to a possibility of infinitely extending the available field: the online and offline space that "we" will occupy in the future would be a space that can never be "itself" and will always be infinite, composed as an interior: at the same time it will always be a conscious representation of something always already missing.

No comments:

Post a Comment